The Anterior Cervical Lip: how to ruin a perfectly good birth

**If you like information in an engaging movie format, check out my Understanding Labour Progress Lesson Package.**

Here is a scenario I keep hearing over and over: A woman is labouring away and all is good. She begins to push with contractions, and her midwife encourages her to follow her body. After a little while, the midwife checks to 'see what is happening' and finds an anterior cervical lip. The woman is told to stop pushing because she is 'not fully dilated' and will damage herself. Her body is lying to her - she is not ready to push. The woman becomes confused and frightened. She is unable to stop pushing and fights her body, creating more pain. Because she is unable to stop pushing, she may be advised to have an epidural. An epidural is inserted along with all the accompanying machines and monitoring. Later, another vaginal examination finds that the cervix has fully dilated and now she is coached to push. The end of the story is usually an instrumental birth (ventouse or forceps) for an epidural-related problem, ie, fetal distress caused by directed pushing; 'failure to progress'; baby malpositioned due to supine position and reduced pelvic tone. The message the woman takes from her birth is that her body failed her, when in fact it was the midwife/system that failed her. Before anyone gets defensive, I am not pointing fingers or blaming individuals, because I have been that midwife. Like most midwives, I was taught that women must not push until their cervix has fully dilated. This theory has been taught to midwives since the 1930s, and even Ina May Gaskin warned against 'early pushing' in Spiritual Midwifery. This post is an attempt to prompt some rethinking about this issue, or rather this non-issue.

Anatomy and physiology

Birth is a complex physiological process, but very simply, two main things occur during labour:

- The uterus changes shape and pulls the cervix over the baby's head

- The baby rotates and descends through the pelvis

But this is not a step-by-step process. It is all happening at the same time, and at different rates. So whilst the cervix is being pulled open by the fundus, the baby is also rotating and descending. Here is a short overview of labour physiology:

Let's have a look at these two aspects of birth physiology with a focus on a cervical lip.

1. Uterus changes shape and pulls the cervix over the baby's head

The cervix does not open as depicted by teaching models, ie, in a nice neat circle. Instead, it is pulled open from the back to the front in an ellipse. The 'os' (opening) is found tucked at the back of the vagina in early labour and opens forward. At some point in labour, almost every woman will have an anterior lip because this is the last part of the cervix to be pulled up over the baby's head. Whether this lip is detected depends on whether/when a vaginal examination is done. A posterior lip is almost unheard of because this part of the cervix disappears first. Or rather it becomes difficult to reach with fingers first.

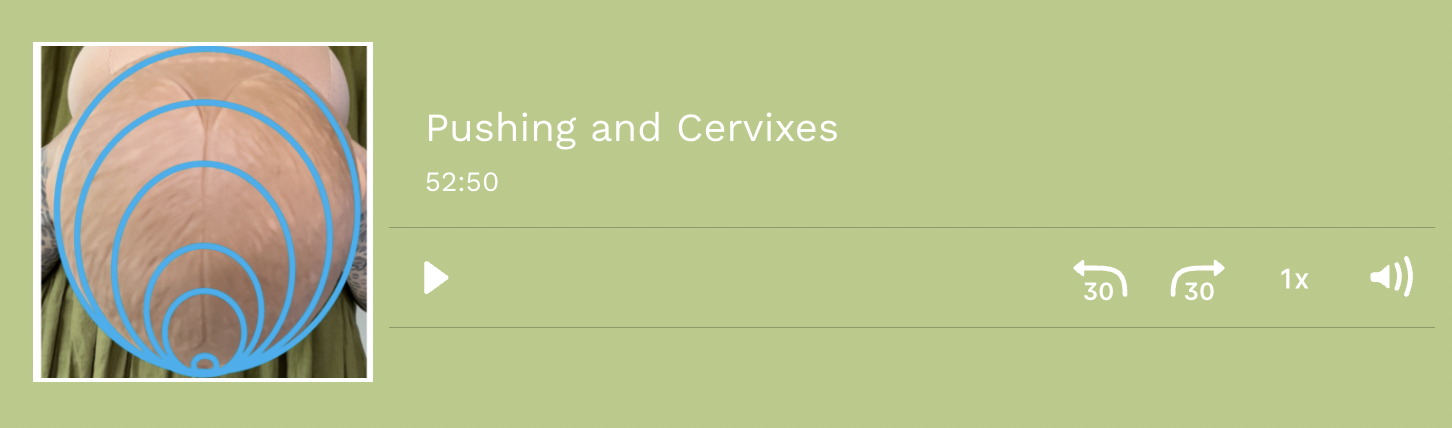

The cervix (in blue) opens in an ellipse from the back of the pelvis to the front (diagrams available here)

The cervix opens because the muscle fibres in the fundus (top of the uterus) retract and shorten with contractions and pull the softer/thinner cervix open. The opening of the cervix does not require pressure from a presenting part, ie, the baby's head or bottom (let's stick to heads for now). However, the head can influence the shape of the cervix as it opens up around it. For example, a well-flexed OA baby (see diagram above) will create a neater, more circular cervix. An OP and/or deflexed baby will create a less-even shape. See this post for more information about how the cervix opens with a baby in an OP position.

2. Rotation and descent of the baby through the pelvis

Babies enter the pelvis through the brim. As you can see from the pictures below, this is easier with their head in a transverse position (facing sideways). As the baby descends into the cavity, their head will be tilted, with the parietal bone/side of the head leading. This is because the angle of the pelvis requires the baby to enter at an angle. Once in the cavity, the baby has room to rotate into a good position for the outlet, which is usually OA. Rotation is aided by pelvic floor shape and tone and often by spontaneous pushing.

The urge to push and I'm talking spontaneous, guttural, unstoppable pushing, is triggered when the presenting part descends deeply into the pelvis and applies pressure to the nerves in the rectum and pelvic bowl. This is sometimes called the 'Ferguson reflex' (named after a man of course) and is not to be confused with the 'fetal ejection reflex' (a term used to describe a very different phenomenon from this spontaneous pushing reflex). The pushing reflex is not dependent on what the cervix is doing, but on where and what the baby's head is doing.

Pushing before full cervical dilation

There is very little research about pushing before full cervical dilation. This is likely to be partly due to the cultural understanding of this as a complication, therefore requiring intervention. Consequently, it would be considered unethical to randomly allocate women to 'no intervention' when they are pushing on an undilated cervix. Unfortunately, physiological birth happens so rarely that even observational studies are primarily of medicalised births (epidural, augmentation, etc.). The other problem is that knowing a woman is pushing before the cervix has finished opening requires a vaginal examination. Therefore, women having undisturbed physiological births are excluded from research, yet these are the births we need to learn physiology from.

Small observational studies have found that the incidence of 'early pushing urge' EPU (as it is referred to in the literature) in hospital settings is between 20% to 40% [1,2]. Interestingly Borrelli et al. [2] found that the sooner the midwife performed a vaginal examination in response to a woman's pushing urges, the more likely they were to find the cervix still there. They also found that 'early pushing' was much more common with primips (first labours). Perhaps because women having their first baby tend to push for longer, therefore be more likely to have a vaginal examination. In the study, early pushing occurred in 41% of women with OP babies.

Spontaneous pushing before the cervix has been pulled up over the baby's head is a normal variation. It is a healthy and helpful physiological process when:

- Baby's head descends into the vagina before the cervix has been pulled over their head. In this case, the additional downward pushing pressure assists the baby to move through the cervix.

- The baby is in an OP position, and the hard, prominent occiput (back of the head) presses on the rectum. In an OA position, this part of the head is against the symphysis pubis, and the baby has to descend deeper before pressure on the rectum occurs from the front of the head. In the case of an OP position, pushing can assist rotation into an OA position. The downward pressure against the shape and tone of the pelvic floor helps the baby pivot.

I am yet to find any evidence that pushing on an unopened cervix will cause damage (and I have searched the research literature including case studies). I have been told many times that it will, but have never seen it happen in my experience of attending births. Borrelli et al. [2] found no cervical lacerations, 3rd-degree tears, or postpartum haemorrhages in the women with an EPU. A review of the available research [3] concluded: 'Pushing with the early urge before full dilation did not seem to increase the risk of cervical edema or any other adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes'. In practice, I have encountered swollen (oedematous) cervixes during labour, mostly in women with epidurals who are unable to move about and before any pushing occurs. I can understand how directed, strong pushing could bruise a cervix. But I don't see how a woman could damage herself by following her urges. Usually, when I dig further into the stories of swollen or bruised cervixes, the women were not having a physiological birth. Often they had Syntocinon (Pitocin) induced contractions and/or directed pushing.

In many ways, the argument regarding pushing, or not, is pointless because once the spontaneous urge takes over it is beyond anyone's control. You either let it happen or start commanding the woman to do something she is unable to do, ie, stop pushing. I can only find one study that examined women's experiences of an 'early' pushing urge [4]. The women in this study were told by their midwives not to push:

In coping with EPU, women found it difficult to follow the midwives’ advice to stop pushing because this was conflicting with what their body was suggesting [to] them. Throughout their attempts to stop pushing, women were accompanied by the conflicting feelings of naturalness of going along with the pushes and discomfort of going against their bodily sensations. Women were confused by the contradiction between their physical perceptions and the need to hold back pushes suggested by the midwife at the same time. Moreover, they reported difficulty in realizing what was happening. This confusion was sometimes related to the feeling of not being believed by health care professionals. (p. 23)

My research into childbirth trauma found that disregarding women's embodied knowledge during labour was disempowering and traumatising [5]. One woman in the study described her experience:

I had the strongest urge to push, the midwife on staff insisted on an internal examination to check dilation, she told me if I pushed now I would end up with an emergency caesarean due to my cervix swelling. She then spent the next hour yelling at me not to push and trying to talk me into an epidural (I was trying my hardest to not push but my body kept taking over). I was begging to be allowed to push….

Telling women to push or not to push is cultural, it is not based on physiology or research. Worse, it disempowers women and reinforces the authority and expertise of the care provider.

When left to get on with their birth, occasionally women will complain of pain associated with a cervical lip being 'nipped' between the baby's head and their symphysis pubis during a pushing contraction. In this case, the woman can be assisted to get into a position that will take the pressure off her cervical lip (e.g., backwards leaning), while undisturbed women usually do this instinctively.

Suggestions

NOTE: This post and the following suggestion relate to physiological, spontaneous labour, not induced, augmented, or medicalised births.

- Don't do routine vaginal examinations (VEs) in labour. What you don't know (that there is a cervical lip) can't hurt you or anyone else. VE's are an unreliable method of assessing progress, and the timelines prescribed for labour are not evidence-based (see this post).

- Ignore pushing and don't say the words 'push' or 'pushing' during a birth. Asking questions or giving directions interferes with the woman's instincts. For example, asking 'are you pushing' can result in the woman thinking... am I? Should I be? Shouldn't I be? Thinking and worrying are counterproductive to oxytocin release and instincts, and therefore birth. If she is pushing, let her get on with it and shush.

- Do not tell the woman to stop pushing. If she is spontaneously pushing (and you have not coached her) she will be unable to stop. It is like telling someone not to blink. Spontaneous pushing will help not hinder the birth. Telling her not to push is disempowering and implies her body is 'wrong'. In addition, after fighting against her urge to push she may then find it difficult to follow her body and push when permitted to do so.

If a woman has been spontaneously pushing for a while with excessive pain (usually above the pubic bone) she may have a cervical lip that is being nipped against the symphysis pubis. There is no need to do a vaginal examination to confirm this unless she wants you to. If you suspect or know there may be a cervical lip:

- Reassure her that she has made fantastic progress and only has a little way to go.

- Ask her to allow her body to do what it needs to, but not to force her pushing.

- Help her get into a position that takes pressure off the lip and feels most comfortable, usually reclining. She may be reluctant to move and may be in a forward-leaning position because it relieves the back pain associated with an OP presentation. This is one of the rare times a suggestion is appropriate.

- If the situation continues and is causing distress, during a contraction the woman can apply upward pressure (sustained and firm) just above the pubic bone in an attempt to 'lift' the cervix up.

- Manually pushing the lip over the baby's head is extremely uncomfortable and may allow the baby's head to move into the vagina before they have rotated which could create further problems. It can also damage the cervix.

Summary

An anterior cervical lip is a normal part of the birth process. It does not require management and is best left undetected. Identifying it and managing the situation as though it were a problem can cause complications.

Further resources

You can find more information on this topic in my Understanding Labour Progress Lesson Package or Reclaiming Childbirth Collective.

Related blog posts

- Vaginal Examinations: stuck on the cervix

- Supporting Women's Instinctive Pushing Behaviour

- Pushing: leave it to the experts

- In Celebration of the OP Baby

Related podcast episode

References

- Downe (2008) The early pushing urge: practice and discourse

- Borrelli et al. (2013) Early pushing urge in labour and midwifery practice

- Tsao (2015) Early pushing before full dilation

- Celesia et al. (2016) Childbearing women's experiences of early pushing urge

- Reed et al. (2017) Women's descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions

Join my mailing list to receive a monthly newsletter containing updates, evidence-based information, musings, rants and other goodies.

You will be sent a confirmation email. If you don't see an email from me in your inbox, check your junk folder and mark my email as 'not spam'.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.