Pre-labour Rupture of Membranes: impatience and risk

**If you like information in an engaging movie format, check out my Amniotic Fluid Lesson Package, where I cover the content below and much more**

The amniotic sac and fluid play an important role in the labour process and usually remain intact until the end of labour. However, around 10% of women will experience their waters breaking before labour begins (Prelabour Rupture of Membranes - PROM). The standard approach to this situation is to induce labour by using prostaglandins and/or syntocinon (pitocin) to stimulate contractions. The term 'augmentation' is often used instead of 'induction' for this procedure. Women who choose to wait are told their baby is at increased risk of infection and they are encouraged to have IV antibiotics during labour.

The rush to start labour and get the baby out after the waters have broken is fairly new. When I first qualified in 2001, the standard hospital advice (UK) for a woman who rang to tell us her waters had broken (and all else was well) was: "If you're not in labour by [day of the week in 3 days time] ring us back." Over the following years, this reduced from 72 hours to 48 hours, then 24 hours, then 18 hours, then 12 hours and now 0 hours. You might assume that this change was based on some new evidence about the dangers involved in waiting for labour. You would be wrong. This post is mainly based on a couple of Cochrane Reviews [1; 2] because hospitals are supposed to base their policies/guidelines on research evidence.

Please note that this post is not about preterm rupture of membranes (before 37 weeks).

Types of Rupture of Membranes

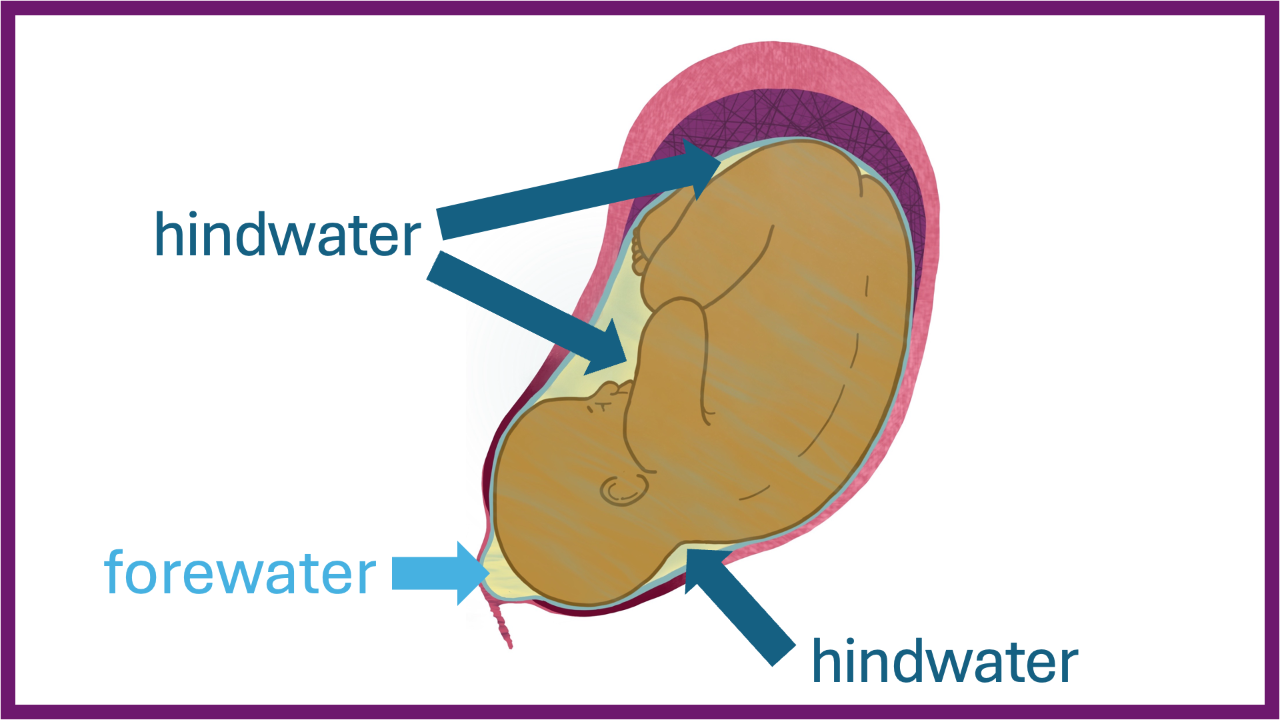

The term 'rupture of membranes' simply means there is a tear/hole in the amniotic sac. Where the hole is will alter how the amniotic fluid leaks out. However, there is no such thing as a 'dry labour' because the baby and placenta keep making amniotic fluid all the way through labour.

See the diagram at the top of this post re. What is considered forewater and hindwater.

Forewater leak

The woman will likely experience a big gush as the fluid between the baby's head and the cervix bursts. The baby's head will move down and plug the cervix, but fluid will keep trickling past their head and through the cervix. Further gushes of fluid can happen if the baby moves their head.

Hindwater leak

This is usually less dramatic than a forewater leak. The hole in the amniotic sac is behind the baby's head, so fluid has to leak out between the amniotic sac and the uterus, past the baby's head and forewaters and out of the vagina. The result is a slow leaking of fluid over time. The forwaters remain intact and function in the same way during labour.

Chorion / Amnion leak

This isn't actually a rupture of membranes at all and often results in a misdiagnosis of PROM. The amniotic sac comprises two separate layers, the chorion (outside layer next to the uterus) and the amnion (inside layer next to the baby). There is around 200ml of fluid and mucous between the two layers, and if the chorion gets a hole in it, but the amnion doesn't, that 'in-between' fluid can leak out. In this case, fluid will leak out like a hindwater leak initially, but won't keep going. Unlike the amniotic fluid, the 'in-between' fluid is not replenished. The amniotic sac is still intact, protecting the baby, and the woman shouldn't be managed as if she has PROM.

Outcomes: induction vs waiting

For Baby

The risk of the baby getting an infection with PROM is 1% compared to 0.5% if there is no PROM. So, 99% of babies will not get an infection following PROM. However, this includes babies who have their birth induced. So, the question is, does inducing labour reduce the general risk of infection after PROM?

A Cochrane Review [1] comparing planned (induced labour) vs expectant (waiting) management concluded that neonatal infection 'may be' reduced with induction. Unfortunately, the research reviewed was not great: "Only three trials were at overall low risk of bias, and the evidence in the review was very low to moderate quality." Indeed, all of the evidence in the review was rated as 'low quality' except for the evidence demonstrating no difference in the death rate for babies between inducing and waiting (this was the only 'moderate quality' research).

Whilst the review reports a slight increase (less than 2%) in 'definite or probable' neonatal sepsis, this needs to be unpicked a little. The difference was no longer significant once the 'probable' portion was removed in the analysis. It would be very interesting to know how many of the suspected (probable) cases of sepsis were merely care providers being cautious and making assumptions. For example, some symptoms associated with sepsis can be caused by other interventions, for example, an epidural increases the chance of a high temperature in both mother and baby; and a stressful labour (and syntocinon) can result in low blood glucose in the newborn. It is common practice to assume infection until proven otherwise and treat accordingly. The fact that there was no difference in Apgar scores between the groups increases my suspicions. Infected babies are much more likely to have a poor Apgar score and require resuscitation at birth.

The review states that "...evidence about longer-term effects on children is needed." There is increasing evidence about the risks of the induction process for babies, which women must consider when making a decision.

For Mother

The Cochrane review [1] did find a slight increase (1%) in the absolute risk of uterine infection for mothers who waited for labour. Bear in mind that these studies were done in hospitals, which are not the best setting when attempting to avoid infection. If a uterine infection is identified early, it can usually be effectively treated with antibiotics. I used to see quite a few uterine infections as a community midwife in the UK doing postnatal home visits, mainly after forceps or ventouse births. However, if the symptoms are missed, the woman does not have access to antibiotics; or the infection is antibiotic resistant, a uterine infection can be life-threatening.

The report found no difference in the rate of caesarean sections. However, the stats for first-time mothers are not separated. This is frustrating because induction significantly increases the chance of a caesarean section for first-time mothers (see this post). Women who have previously given birth have no increased chance of a caesarean section with induction. When you mix the two groups together (like most research does), you miss the outcomes for those first-timers.

Only one of the trials in the Cochrane Review [1] bothered to ask women what they thought of their experience (no surprises there). In this trial, women who had their labour augmented were more likely to tick the box saying that there was 'nothing they disliked in their management'. There are huge limitations when using surveys to assess experiences, and a good qualitative study is needed here. For example, how can a woman compare one experience (induction) against an experience they did not have (physiological labour)? You don't know what you don't know. Also, if a woman believes she is protecting her baby against infection by inducing labour, this may influence her perception of the management. The Cochrane Review states that no trials reported on maternal views of care, or postnatal depression.

Antibiotics Just in Case?

A Cochrane Review [2] of antibiotics for pre-labour rupture of membranes at or near term concluded that: "There is not enough information in this review to assess the possible side-effects from the use of antibiotics for women or their infants, particularly for any possible long-term harms. Because we do not know enough about side-effects and because we did not find strong evidence of benefit from antibiotics, they should not be routinely used for pregnant women with ruptured membranes prior to labour at term, unless a woman shows signs of infection."

So it appears that women and babies are being given high doses of antibiotics during labour without sufficient evidence to support the practice. In addition, these antibiotics may have short-term, and long-term side effects. As a student midwife, I was asked by a mother what would happen if her unborn baby was allergic to antibiotics. I had no idea, so I asked the consultant, and after a long and complex answer, I realised he didn't know either. However, most side-effects are more subtle than anaphylaxis. The effect I most often see is oral thrush in the baby and co-existing nipple thrush for the mother, and subsequent breastfeeding problems. However, there are potential long-term problems associated with antibiotic exposure and the disruption of gut microbiota, affecting the integrity of the immune system. Another issue is the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria due to the overuse of antibiotics, which can make infections (e.g. uterine) difficult to treat.

Choosing to Wait

Women need to be given adequate information so that they can make the decision that is right for them. I'm not sure most women are fully informed, and instead are told their baby is 'at risk'. As we know, you can get a mother to do anything if she believes it is in the best interests of her baby. So what happens if a woman chooses to wait for labour? Most women (79%) will go into labour within 12 hours of their waters breaking and 95% will be in spontaneous labour within 24 hours [3].

Ashlee, whose birth I attended, has given me permission to share her experience and photo here. Ashlee's daughter Arden taught her family and midwives about patience and trust. We waited 63 hours from waters breaking to welcome her into the world. After a 2 hour, 20 minute labour she was born through water and into her mother's arms. I wonder how different this birth would have been if Ashlee had followed hospital guidelines. Instead she weighed up the information for herself and chose to stay home amongst her familiar bacteria, and let her daughter decide when she was ready to be born.

Suggestions for waiting:

- View the situation positively. We are all getting time to prepare for the birth and the baby's arrival. The mother can use the time to relax, sleep, and be pampered.

- The vagina self cleans downwards. Reduce the chance of infection by not putting anything into the vagina ie. no vaginal examinations. If a vaginal examination is absolutely necessary sterile gloves must be used.

- A warm bath (without anything added to the water) is fine if the woman wants that. The vagina is good a stopping water from getting into the uterus.

- Be self-aware, connect with your baby, and let your midwife/care provider know of any changes, such as feeling unwell, a high temperature, changes in the colour or smell of the amniotic fluid, or any reduction in the baby's movements.

- Most importantly trust the process. Birth will happen.

- Once the baby is born, keep the baby skin-to-skin with the mother to reduce the chance of infection by allowing the baby to become colonised by the mother's bacteria (this applies to all births).

- After birth, be aware of signs of infection. Mother: fever, raised pulse, feeling unwell, smelly vaginal discharge, uterine pain. Baby: fever, noisy breathing, change in colour (pale), listless.

Summary

The research evidence regarding induction for rupture of membranes is poor. Giving antibiotics in labour 'just in case' is not supported by current evidence, and may cause problems for baby and mother. Women need adequate information on which to base their decisions regarding the management, or not, of this situation. Women who choose to wait for labour should be supported in doing so.

Further Resources

You can find more information on this topic in my Amniotic Fluid Lesson Package or Reclaiming Childbirth Collective.

Related blog posts

- In Defence of the Amniotic Sac

- Amniotic Fluid Volume

- Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid: variation or complication?

- Induction: a step by step guide

- In Celebration of the OP Baby

Related podcast episodes

References

- Middleton et al. (2017) Planned early birth versus expectant management (waiting) for prelabour rupture of membranes at term (37 weeks or more)

- Wojcieszek et al. (2014) Antibiotics for rupture of membranes when a pregnant woman is at or near term but not in labour

- Middleton et al. (2017) Is it better for a baby to be born immediately or to wait for labour to start spontaneously when waters break at or after 37 weeks)

Join my mailing list to receive a monthly newsletter containing updates, evidence-based information, musings, rants and other goodies.

You will be sent a confirmation email. If you don't see an email from me in your inbox, check your junk folder and mark my email as 'not spam'.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.