Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid: variation or complication?

**If you like information in an engaging movie format, check out my Amniotic Fluid Lesson Package, where I cover the content below and much more**

When meconium is noticed in amniotic fluid during labour, it often initiates a cascade of interventions. A CTG machine will often be strapped onto the woman, reducing her ability to move and increasing her chance of having a c-section or instrumental birth. Time limits for labour may be tightened up further, resulting in induction or augmentation, which increases the chance of fetal distress and for first-time mothers, a c-section. As the baby is being born, they may be subjected to airway suctioning which can cause a vagal response (heart rate deceleration) and difficulties with breastfeeding. Once born, the baby is likely to have their umbilical cord cut prematurely and be given to a paediatrician who may also suction the baby's airways. In the first 24 hours after birth, the baby will be disturbed regularly to have their temperature, breathing and heart rate assessed. In some hospitals, the baby will be taken away from their mother to be observed in a nursery.

This is a lot of fuss for a bit of poop which in the vast majority of cases is not a problem. Indeed, many of the interventions implemented because of the meconium are more likely to cause complications than the meconium itself.

This post is mainly based on two journal articles: one by Unsworth & Vause [1] was published in an obstetric journal, and the other by Powell [2] published in a midwifery journal. Both articles agree that very little is known about meconium and whether it is a problem at all.

Meconium Facts

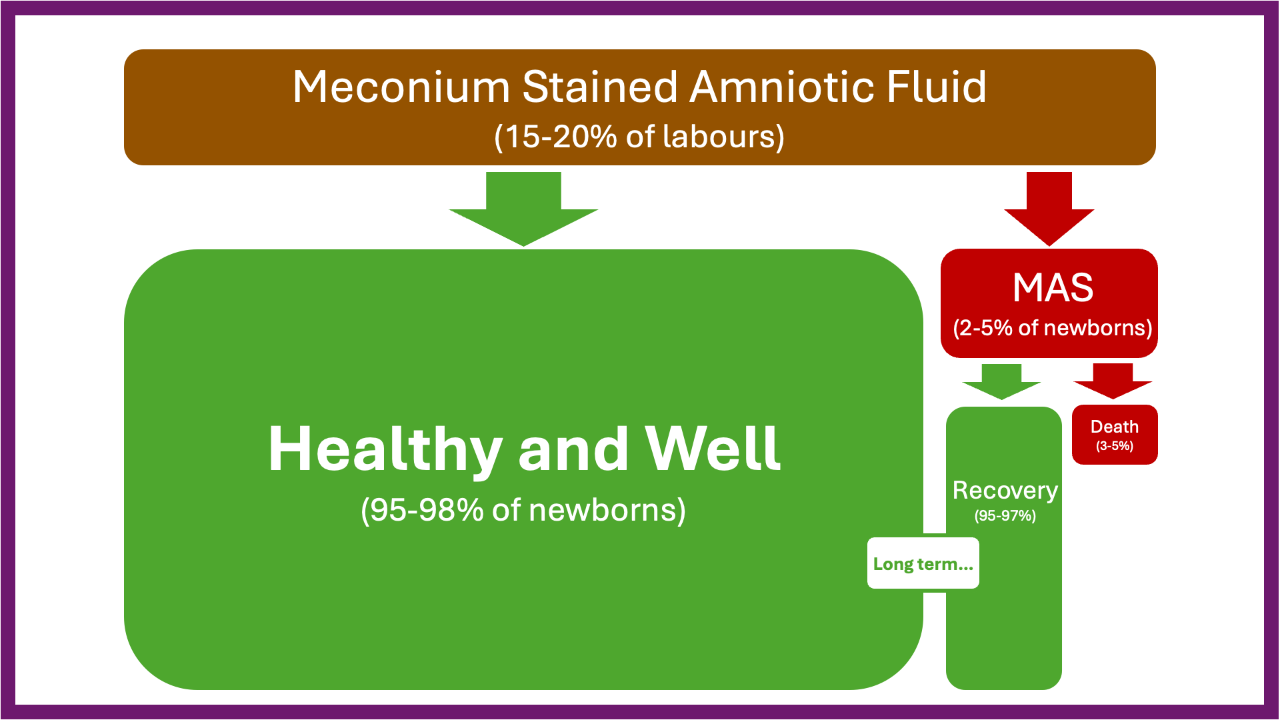

Meconium is a mixture of mostly water (70-80%) and a number of other interesting ingredients (amniotic fluid, intestinal epithelial cells, lanugo, etc.). Around 15-20% of babies are born with meconium stained amniotic fluid.

There are five reasons (theoretically) that a baby may open their bowels before birth:

- The digestive system has reached maturity and the intestine has begun working, ie, moving the meconium out (peristalsis). This is the most common reason – 15-20% of term babies and 30-40% of post-term babies will have passed meconium before birth.

- The umbilical cord or head is being compressed (during labour), ie, a vagally mediated gastrointestinal peristalsis. This is a normal physiological response and can happen without fetal distress. It may be why a lot of babies pass meconium as their head is compressed during the last minutes of birth and then arrive with a trail of poop behind them.

- If the baby is in a breech position, compression of the abdomen as their bottom moves through the vagina usually squeezes out meconium.

- In cases of Intrahepatic cholestasis during pregnancy, the baby may pass thin meconium. This may be due to the increased movement of fluids through the baby's bowel caused by bile acids.

- Fetal distress resulting in hypoxia. However, the exact relationship between fetal distress and meconium stained fluid is uncertain. The theory is that intestinal ischaemia (lack of oxygen) relaxes the anal sphincter and increases gastrointestinal peristalsis. However, fetal distress can be present without meconium, and meconium can be present without fetal distress.

Bear in mind that these are theories without evidence to support them. Indeed, in 'animal models, ' the theory that hypoxia results in meconium is incorrect. There are also other theories about meconium in pregnancy—that the baby continually passes it and clears it—but I think this post is confusing enough without wading into them (see the key articles for further information).

Meconium alone cannot be relied on as an indication of fetal distress: "... meconium passage, in the absence of other signs of fetal distress, is not a sign of hypoxia..." [1]. An abnormal heart rate is a better predictor of fetal distress, and an abnormal heart rate + meconium may provide an even better indication that a baby may be in trouble. In addition, thick meconium rather than thin meconium is associated with complications. In summary, it is important to remember that:

- Most babies who are born in a poor condition do not have meconium stained amniotic fluid.

- Most babies with meconium stained amniotic fluid are born in good condition.

Despite this, babies who are known to have passed meconium (of any variety) without any other risk factors are treated as if they are in imminent danger. I am guessing this is because if a previously unstressed baby becomes hypoxic during labour, it may result in MAS.

Meconium Aspiration Syndrome (MAS)

MAS is the primary concern when meconium is in the amniotic fluid. It is an extremely rare complication - around 2-5% of the 15-20% of babies with meconium stained amniotic fluid will develop MAS [1]. Of the 2-5% of the 15-20%, 3-5% of babies will die. OK enough %s of %s – basically MAS is very rare but can be fatal. For those who like numbers, if you have meconium in your amniotic fluid, your baby has a 0.06% (1:1667) chance of dying from 'MAS'. This risk will go up and down depending on individual circumstances, eg, prematurity, congenital abnormalities, additional labour complications, etc.

MAS occurs when the baby inhales meconium stained amniotic fluid during labour, birth or immediately following birth. Babies make shallow breathing movements during pregnancy. Breathing movements slow down in response to prostaglandins before birth. For a baby to gasp in-utero they must be extremely asphyxiated. This is unlikely to happen without anyone noticing the baby is in trouble, ie, an abnormal fetal heart rate during auscultation and an abnormal labour (or induced contractions). A baby can maintain aerobic metabolism until oxygen levels at the placental blood exchange site drop 50% below normal levels. The baby then undergoes a number of physiological compensatory responses and if the oxygen level does not improve, or worsens they will descend through hypoxaemia, hypoxia, anaerobic metabolism, metabolic acidosis, asphyxia, and then become 'unconscious' at which point his limbic system will initiate a gasp in an attempt to get oxygen. I cover fetal distress in more detail in my Medical Birth Lesson Package.

Meconium in the lungs can cause problems with respiration and increase the risk of infection. For 3-5% of these babies it can result in death, but remember there are often other issues occurring along with the MAS, eg prematurity or fetal growth restriction. So, meconium alone is not a problem. Meconium + an asphyxiated baby = the possibility of MAS

Risky Interventions for Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid

So you would think that the sensible thing to do if a baby has passed meconium (for whatever reason) is to create conditions that are least likely to result in asphyxia and MAS. However, common practice is to do things that are known to cause hypoxia, for example:

- Inducing labour if the waters have broken (with meconium present) and there are no contractions, or if labour is 'slow' in an attempt to get the baby out of the uterus quickly.

- Performing an ARM (breaking the waters) to see if there is meconium in the waters when there are concerns about the fetal heart rate.

- Directed pushing to speed up the birth.

- Having extra people in the room (paediatricians), bright lights and medical resus equipment, which may stress the mother and reduce oxytocin release.

- Cutting the umbilical cord before the placenta has finished supporting the transition to breathing in order to hand the baby to the paediatrician.

Suctioning the baby's airways

Evidence-based clinical guidelines generally recommend NOT suctioning a baby's airways unless they are unresponsive, floppy and require resuscitation. Then only suctioning using a laryngoscope so that you can see what you are doing.

Suctioning at birth does not reduce the risk of MAS [3] and may cause the baby to gasp, i.e., inhale deeply. This is precisely what you are trying to avoid with meconium-stained amniotic fluid. For any baby, meconium or no meconium, suctioning is likely to be a very unpleasant experience.

The physiological process of birth takes care of the mucous and amniotic fluid (and meconium) in the baby's airways. As the baby's head is born and waiting for the next contraction, the chest is compressed, and gravity helps drain the fluid. Babies born by c-section miss out on this and are more likely to have problems associated with fluid in their airways and stomach.

Suggestions

All babies deserve to have the least stressful arrival possible. It is even more critical that a baby who has passed meconium does not become stressed during labour and birth because it could lead to MAS. The following suggestions apply to all births, including when there is meconium stained amniotic fluid:

- Avoid an ARM during labour so that any meconium present is not known until the membranes rupture spontaneously (hopefully, this will happen after much of the labour is complete). If meconium is present, it will remain well diluted, and the amniotic fluid will protect the baby from compression during contractions.

- Ensure that the mother knows meconium is a variation and not necessarily a complication. The practitioner needs to consider the holistic picture—a post-dates baby with old meconium is very different from a 38-week baby with thick, fresh meconium and fetal heart rate abnormalities.

- If this is a concerning scenario, ie, not post dates and thick meconium, or fresh meconium occurring during labour, then increased monitoring and/or medical intervention may be required.

- Otherwise, create a relaxing birth environment.

- Avoid any interventions that are associated with fetal distress – ARM, syntocinon/pitocin, directed pushing.

- In the hospital, do not allow others into the room unless the mother wants them there. If there is a policy to have a paediatrician present, they can wait outside the room to be called if needed.

- To assist with airway clearing, encourage a slow birth of the baby's head in a position that allows drainage of the airways (e.g., the mother is not lying on her back). Do not pull the baby out.

- Once the baby is born, leave the umbilical cord intact until it stops pulsing to allow a gentle transition to breathing.

- Keep baby skin to skin with mother following birth.

- Encourage the mother to let you know if she is concerned about her baby in any way over the next 24 hours (eg, feeling hot, noisy breathing, etc.)

Summary

Meconium is not dangerous unless the baby inhales it. However, for some babies, meconium is a sign of hypoxia, and they are at risk of meconium aspiration. These babies need additional monitoring and perhaps medical intervention. For most babies, i.e., those who are post-dates, meconium is a sign of a mature digestive system that has begun to function. In these cases, the aim should be to avoid hypoxia during labour and, therefore, meconium aspiration.

Further Resources

You can find more information on this topic in my Amniotic Fluid Lesson Package or Reclaiming Childbirth Collective.

Related blog posts

Related podcast episode

References

Join my mailing list to receive a monthly newsletter containing updates, evidence-based information, musings, rants and other goodies.

You will be sent a confirmation email. If you don't see an email from me in your inbox, check your junk folder and mark my email as 'not spam'.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.