The Effective Labour Contraction

**If you like information in an engaging movie format, check out my Understanding Labour Progress Lesson Package, where I cover the content below and much more**

One of my failings as a midwife was my inability to assess the strength and effectiveness of a uterine contraction. This presented a problem in the hospital setting as midwives are often asked 'how strong are her contractions?' or 'is she having effective contractions?' I spent many hours as a student midwife with my hands on women's abdomens attempting to assess their contractions. Not only was I unsuccessful, but I was probably very irritating and disrupted physiology (apologies to those women). This post discusses whether it is possible to determine the effectiveness of contractions, and whether we need to.

A Quick History Lesson on Labour Progress

The idea that birth should be efficient has its roots in the 17th century, when physicians used science to redefine birth. The body was conceptualised as a machine, and birth became a process consisting of stages, measurements, timelines, mechanisms, etc. This is still reflected in current textbooks, knowledge, and practice.

In the 1950s Emanuel Friedman created a graph of labour based on his research of 500 women having their first baby [1]. These women were subjected to rectal examinations every hour during their labour (you can apparently feel the cervix through the rectum). Most of the women in the study were sedated, and had medication (Pitocin) to speed up their labour and 55% had a forceps birth. The final graph is the basis for modern assessments of labour progress. However, there are variations between hospital policies regarding adequate progress. For example, a cervix can open 0.5cm an hour in one hospital and be adequate, whereas in another it must open 1cm per hour to be adequate. Now I could write an entire post (and might do so in the future) on the ridiculous notion that you can apply a graph to something as complex and unique as a birthing woman (edit: I wrote a book instead). However, I think the evidence speaks for itself. More than half of all women who experience labour in Australia have their labour either induced or augmented [2]. Therefore, inadequate progress is the norm or our definition of adequate progress is wrong.

How a Contraction Works

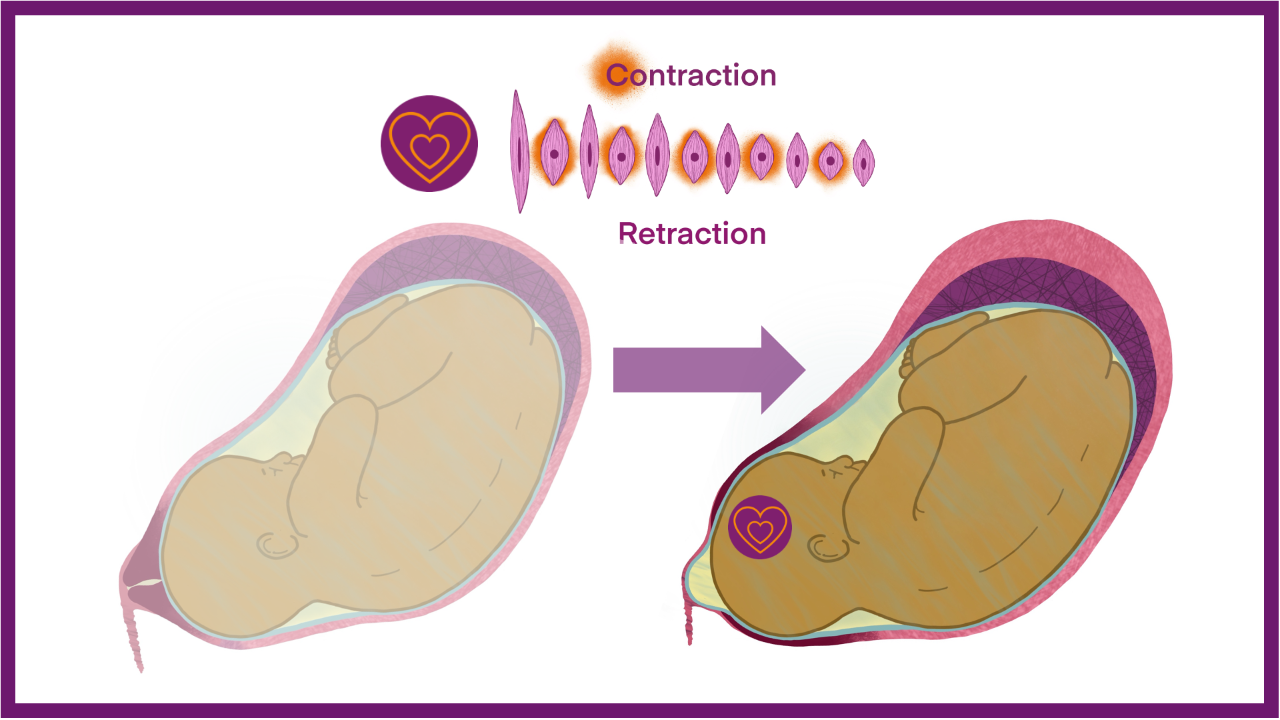

The hormone oxytocin (heart) regulates contractions, and it is released from the hypothalamus (primitive brain). The uterus has oxytocin receptors that respond to oxytocin by initiating contractions. Contractions start in the top of the uterus (fundus) and 'wave' downwards. The cervix must be ready (ie, ripe) before it will respond to contractions by opening. This is why induction usually involves preparation of the cervix with prostaglandins before starting a syntocinon (pitocin) drip to create contractions. When the uterus contracts, the placental circulation is reduced (more so if the waters have broken), slightly decreasing the oxygen supply to the baby. This is why there are breaks in between contractions – to allow the baby to rebalance their oxygen levels before the next contraction. I cover this in more detail in my Childbirth Physiology Course and my book.

Note: Oxytocin (syntocinon/pitocin) administered via a drip is not released in waves and an individual woman's oxytocin receptor response is unpredictable. This may result in contractions that are too powerful without an adequate gap between them, leading to a hypoxic baby.

Feelings and behaviour influence oxytocin, which is part of the hormonal cocktail that prepares a mother and baby for bonding and attachment. The hormonal formula is oxytocin (love) + beta-endorphin (dependency) + prolactin (mothering) = mother-baby bond.

Note: Oxytocin does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Therefore, only oxytocin produced in the brain has these psychological/emotional effects. Syntocinon/pitocin administered via a drip into the bloodstream only acts on the uterus, ie, contractions.

Contraction Pattern

Contractions are measured according to how often they occur in a 10 minute period and are recorded as 2:10, 3:10, 4:10 etc. To be considered 'effective,' contractions must occur 3:10 or more and last for 45 seconds or more. From a mechanistic perspective, it would be impossible to progress through labour with two contractions or less every 10 minutes. I actually believed this for some time until women showed me otherwise.

What I now know is that a woman's contraction pattern is unique. I have witnessed women birth babies perfectly well with very 'ineffective' contraction patterns. The ones that stand out in my mind are: A woman with an OP baby whose contractions never got closer than 5 minutes apart and were mostly 7-10 minutes apart. And a first-time mother who gave birth to her baby with mostly 10-minute spaces between contractions. When left to birth physiologically, women's labour patterns are as unique as they are.

Physiological plateaus during labour are also common in undisturbed birth, with contractions slowing and stopping. A study by Weckend et al. explored this phenomenon and concluded [3]:

"This study challenges the widespread bio-medical conceptualisation of plateauing labour as failure to progress, encourages a renegotiation of what can be considered healthy and normal during childbirth, and provides a stimulus to acknowledge the significance of childbirth philosophy for maternity care practice."

Unfortunately, many midwives are unable to witness a variety of contraction patterns because individuality is not tolerated in the hospital setting.

Contraction Strength

I have already mentioned that I don't believe you can do this by touch. Observing a woman may give you some idea, especially if you have seen a change in her behaviour (sound, movement etc.) over time and/or know her well. But again this is subjective and I'm sure many midwives have been caught out by women who appear to be doing 'nothing', but actually are, or appearing to be about to birth when they are not. Using dilation of the cervix to determine the effectiveness of contractions is also unhelpful (see this post about routine vaginal examinations).

Sensible Assessment of Contractions

Spontaneous labour

I wrote about the holistic assessment of labour progress in another blog post and cover it in my Understanding Labour Progress Lesson Package. In this post, I focus on contraction patterns.

Every woman's contraction pattern is unique, and routinely applying graphs does not improve outcomes and leads to unnecessary intervention. Physically obstructed labour is rare but can be identified by frequent, long-lasting contractions over many hours with no change in the pattern of labour or position of the baby. Women often 'know' there is something 'wrong'. Eventually, the baby may begin to show signs of distress.

Facilitating an environment that promotes the woman's oxytocin release will make contractions more effective. Fussing about with the woman's abdomen and watching her will reduce oxytocin release.

Induced or augmented labour

Over-contraction and/or fetal distress are common complications associated with using syntocinon/pitocin in labour. A CTG machine must be used to monitor the baby's heart rate closely. A midwife should also use her hands to assess how often contractions occur, and for how long, because CTG machines are not very good at this. Again, CTG machines, like midwives, can only tell you how often contractions occur and hint at how long they last. In this case, the assessment of contractions is aimed at avoiding too little space between contractions because this results in fetal distress. With an induced labour the aim is usually to have three contractions in ten minutes.

Summary

Care providers cannot assess the effectiveness or strength of a contraction. An effective labour pattern is one where the mother and baby are well, and some progress is made over time. Instead of assessing contractions, midwives should concentrate on creating an environment that supports oxytocin release.

Further Resources

More information on this topic is available in my Understanding Labour Progress Lesson Package, Childbirth Physiology Course, or Reclaiming Childbirth Collective.

Related blog posts

- Understanding and Assessing Labour Progress

- The Assessment of Labour Progress

- Vaginal Examinations: stuck on the cervix

- Early Labour and Mixed Messages

- Supporting Women's Instinctive Pushing Behaviour

Related podcast episode

References

Join my mailing list to receive a monthly newsletter containing updates, evidence-based information, musings, rants and other goodies.

You will be sent a confirmation email. If you don't see an email from me in your inbox, check your junk folder and mark my email as 'not spam'.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.