Active Management of the Placenta

**If you like information in an engaging movie format, check out my Early Integration Phase Lesson Package, where I cover the content below and much more**

Postpartum haemorrhage is historically and globally the leading cause of maternal death [1]. The most dangerous time for a woman during the birth process is after her baby is born, around the time the placenta is birthed. While the mother and baby meet face to face, and the family greets their new member, there is a lot of important work going on behind the scenes (inside the woman).

The Physiology of Placental Birth

This is an overview of what happens to ensure the placenta is born and the blood vessels feeding the placenta stop bleeding. I cover the physiology of childbirth in-depth in my book Reclaiming Childbirth, my online course Childbirth Physiology and my Early Integration Phase Lesson Package. The following is an overview:

Before the baby is born

At the end of pregnancy, the structure and biochemistry of the placenta changes. Recently, there has been discussion about how these changes may facilitate the separation of the placenta from the uterus after birth. This would make sense because pre-term and early term births are more likely to have problems with the separation of the placenta from the uterine wall. I have written more about this in another post.

Birth does not happen in distinct stages and the birth of the placenta is part of a complex process that begins before the baby is born. Oxytocin makes the uterus contract. Oxytocin is released by the posterior pituitary gland (in the brain) during labour to regulate contractions. It is one of the key birthing/bonding hormones. As the birth of the baby becomes imminent, high levels of oxytocin are circulating in the mother's bloodstream. This creates strong uterine contractions which move the baby through the vagina, and prepare the mother and baby for post-birth bonding behaviours.

After the baby is born

Pathology – when it doesn't work

The bottom line is that the birth of the placenta and haemostasis (prevention of excessive bleeding) depend on effective uterine contraction. Ineffective uterine contraction is the leading cause of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH). Other causes are perineal/cervical damage or, even more rarely, clotting disorders.

There are two causes of ineffective uterine contraction after birth:

- Hormonal: Inadequate circulating oxytocin or inadequate uterine response to oxytocin. Inadequate response is often because the oxytocin receptors in the uterus have become saturated by large doses of syntocinon over a long period of time during an induction [2; 3].

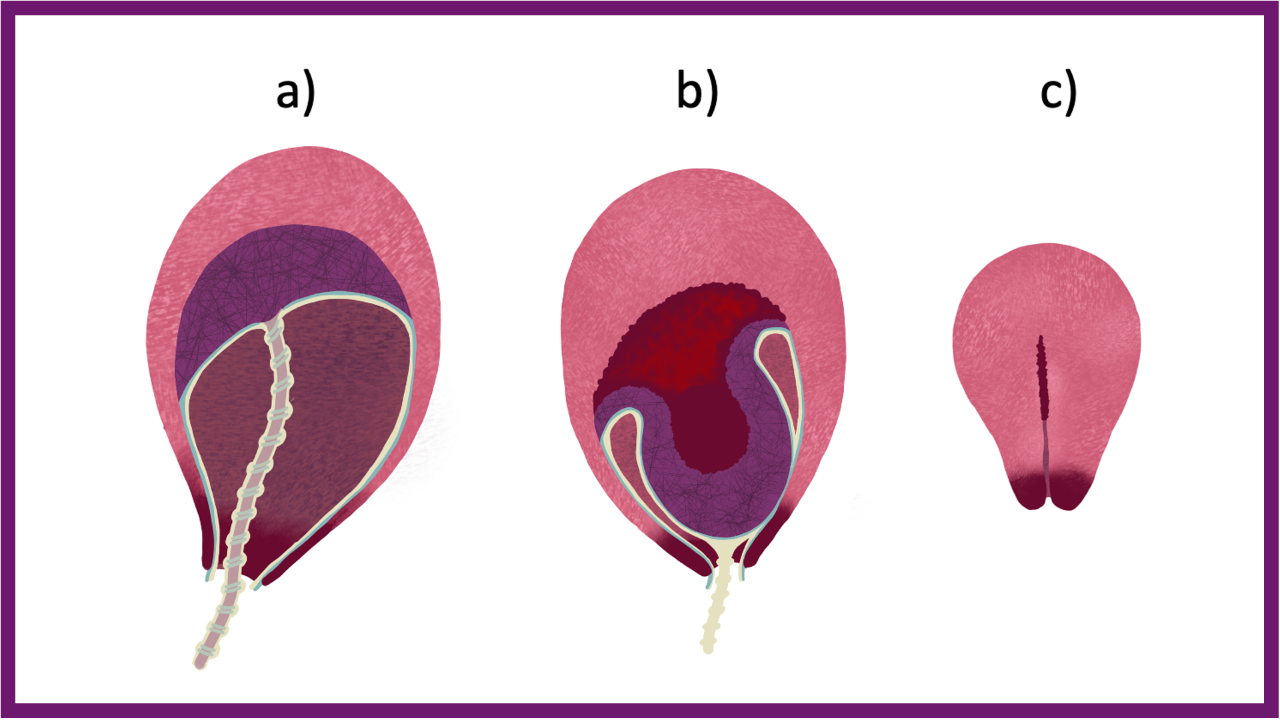

- Mechanical: Something is in the way, and the uterus cannot contract. Most often, this is a full bladder taking up space in the pelvis and stopping the uterus from contracting. However, it can also be a large clot in the uterus or a partially detached placenta.

Most PPHs occur after the placenta is out. PPH can and does occur after a c-section too. In fact it is more likely after c-section than vaginal birth.

Another complication can be a retained placenta, ie, the placenta remains attached. The definition of a retained placenta varies – and I'm not game to put a timeframe on it. However, once you have done something (such as given an oxytocic drug) you need to finish the job and get the placenta out. If you have not, and there is no bleeding or concerns about the woman, then how long is a piece of string?

Active Management of Placental Birth

In the 1950s syntocinon (pitocin) hit the birth scene. Syntocinon is an artificial version of oxytocin and is now used extensively for induction of labour, augmentation of labour and to 'actively manage' the birth of the placenta. It differs from endogenous oxytocin in the way it is released into the blood stream – ie, in a consistent dose rather than in pulse-like waves. Syntocinon is also unable to cross the maternal blood-brain barrier and influence instinctive bonding behaviour.

When used for active management of the placenta, syntocinon mimics the physiology described above by initiating uterine contractions. How active management is carried out varies considerably [4], which drives midwifery students mad. Different practitioners do their own thing, and the literature is also inconsistent. Essentially syntocinon (10iu) is given to the mother by injection after the birth of the baby (although sometimes syntometrine). The cord is clamped and cut, and the placenta is usually pulled out using controlled cord traction. The order and timing of these interventions varies, although pulling the placenta out obviously comes last. The areas of debate/negotiation are:

- Timing of injecting syntocinon: Originally, syntocinon was given with the birth of the baby's anterior shoulder. Nowadays, it seems to be given after the birth of the baby. There is no research determining the best time. Syntocinon takes around 3 mins to work when given IM (into muscle), so in theory, to mimic physiology, it should probably be given soon after the baby arrives. However, there is no evidence to support early administration of syntocinon. In fact, the research suggests that giving the oxytocic before or after the birth of the placenta makes no difference to the risk of PPH [5].

- Timing of clamping and cutting the cord: The risks of premature cord clamping are now well known, and a Cochrane review recommends delaying cord clamping [6]. Most midwives I know (regardless of where they work) wait until the cord has stopped pulsing before clamping. Some are concerned about syntocinon crossing the placenta into the baby. However, syntocinon does not cross the placenta as previously thought. There is also a theory that the strong contraction caused by syntocinon will shunt excess blood from the placenta to the baby. Again, there is no evidence that this happens, and during physiological birth, all of the blood transfers to the baby – there is no 'excess' blood to shunt. There is also no evidence that waiting to clamp the cord increases the risk of jaundice [7].

- Whether to 'drain' the placenta: If the cord has been prematurely clamped, some of the baby's blood is trapped in the placenta – this makes the placenta bigger and more bulky, and in theory/experience more difficult to get out. There is no research to support this, but many midwives will leave the placenta end of the cord unclamped and drain the trapped blood before attempting to deliver the placenta. Of course, it is even better if all that blood is in the baby leaving the placenta empty.

- Whether or not controlled cord traction (CCT) is used and when: Pulling the placenta out after syntocinon has been injected and the umbilical cord has been cut is standard practice. Some midwives wait until they have seen signs of placental separation before pulling (trickle of blood and lengthening of the cord). I think this part of active management causes the most problems. If you pull on a placenta that has not yet separated, you can partially detach it = some blood vessels are 'torn and open', but the uterus cannot contract because the placenta is in the way. Or, you can detach it before the syntocinon is working, i.e., no contractions are happening to stop the bleeding. Or worse case, and very rare scenario, you can pull the uterus out (inverted uterus)! More commonly, you can snap the umbilical cord – which often freaks everyone out. But a snapped cord is not a big drama. It just means the mother will have to get up and push her placenta out, which brings me around to the idea of not pulling at all. A study by found that the 'omission of controlled cord traction' did not increase the risk of severe haemorrhage (they only looked at severe) [8]. Another study found that CCT made no difference in the PPH rate and concluded that CCT made no difference [9]. So, women should have the option of getting upright and pushing, or having someone pull their placenta out for them. Or even perhaps pulling their placenta out?

Active management is usually (not always) quicker than physiological. This is probably another reason it is favoured in hospital settings. Less time waiting for a placenta = less time stressing about a potential PPH, and you can get the woman to the next station (postnatal ward) quicker.

Occasionally, syntometrine, a combination of syntocinon and ergometrine, is used for active management. However, it is not generally used nowadays because ergometrine acts on all smooth muscle, not just the uterus. Therefore, the side effects are vomiting, raised blood pressure, and potentially a retained placenta due to the cervix shutting—although I'm not convinced that the cervix closes firmly enough to trap a squishy placenta.

What the Research Tells Us, and Doesn't Tell Us

The expectant vs active management of the 'third stage' has been going on since I was a student midwife (I did a literature review on it as an assessment). Today, I am doing it the easy way and relying on Cochrane to review the studies on hospital births for me.

Birth in a medicalised setting

Both Cochrane reviews [10; 11] found that active management was not effective at reducing significant PPH for low risk women. When interpreting the review findings, it is important to remember that all of the studies included were conducted in a hospital setting. The experimental group had 'expectant' management, meaning that the practitioners attending were not carrying out their usual routine interventions and instead were waiting for the placenta to birth. They may have been unprepared for, or uncomfortable with this approach because care providers in hospital settings can be inexperienced at supporting physiological placental birth [4; 12]. This may have influenced outcomes. In addition, the quality of the research in the review was low quality. In conclusion [10]:

"Although the data appeared to show that active management reduced the risk of severe primary PPH greater than 1000 mL at the time of birth, we are uncertain of this finding because of the very low‐quality evidence. Active management may reduce the incidence of maternal anaemia (Hb less than 9 g/dL) following birth, but harms such as postnatal hypertension, pain and return to hospital due to bleeding were identified.

In women at low risk of excessive bleeding, it is uncertain whether there was a difference between active and expectant management for severe PPH or maternal Hb less than 9 g/dL (at 24 to 72 hours). Women could be given information on the benefits and harms of both methods to support informed choice. Given the concerns about early cord clamping and the potential adverse effects of some uterotonics, it is critical now to look at the individual components of third‐stage management."

Birth in a physiology-supportive setting

Women with care providers experienced in supporting physiology have very different outcomes. A study compared active vs holistic expectant management in a setting where the midwives were experienced with physiological placental births [13]. Active management was associated with a seven to eight fold increase in PPH rates compared to a holistic physiological approach. Another retrospective study found a twofold increase in large PPHs (1000mls+) for low-risk women having an actively managed placental birth in New Zealand compared to those having a physiological placental birth [14]. In summary, for women having undisturbed physiological births, active management of the placenta increases their chance of having a PPH.

As previously described, the baby plays an important role in assisting with the birth of the placenta. Therefore, undisturbed interactions between mother and baby are important in avoiding a PPH. A recent study looked at the impact of removing babies from their mother after birth and found that: "women who did not have skin to skin and breast feeding were almost twice as likely to have a PPH compared to women..." who did have this contact with their baby [15]. The authors conclude: "...this study suggests that skin to skin contact and breastfeeding immediately after birth may be effective in reducing PPH rates for women at any level of risk of PPH."

An interesting study compared PPH rates between planned hospital birth vs planned homebirth. They adjusted for co-founders such as risk factors associated with PPH. The study found lower rates of PPH for women planning homebirth, even if transferred to hospital during labour or afterwards. The authors conclude: "Women and their partners should be advised that the risk of PPH is higher among births planned to take place in hospital compared to births planned to take place at home, but that further research is needed to understand (a) whether the same pattern applies to the more life-threatening categories of PPH, and (b) why hospital birth is associated with increased odds of PPH. If it is due to the way in which labour is managed in hospital, changes should be made to practices which compromise the safety of labouring women."

Suggesting for Reducing the Chance of a PPH

A safe and effective physiological placental birth requires effective endogenous oxytocin release. This is facilitated by:

- A physiological birth of the baby: No interventions during the birth process, eg, induction, augmentation, epidural, medication, instructions or complications.

- An environment that supports oxytocin release includes privacy, low lighting, warmth, and comfort. Strangers, such as paediatricians or extra midwives, should not enter the birth space.

- Undisturbed skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby: others must not handle the baby or engage the mother in conversation. These mother-baby interactions may result in breastfeeding, but this should not be 'pushed' as not all babies want to breastfeed immediately.

- No fiddling: No feeling the fundus (uterus). No clamping, cutting or pulling on the umbilical cord. No clinical observations or 'busying' around the room.

- No stress and fear: Those in the room must be relaxed. The midwife needs to be comfortable with waiting and have patience. The mother must not be stressed as adrenaline inhibits oxytocin release. This is why a PPH often occurs after a complicated birth (eg, shoulder dystocia) and when the baby needs resuscitating.

- No prescribed timeframes: Many hospital policies require intervention within half an hour if the placenta has not birthed. This is not helpful and generates anxiety, which is counterproductive.

The most important factor in ensuring a safe physiological birth of the placenta is a physiological birth of the baby.

However, in Australia, less than a quarter of women go into spontaneous labour and continue to labour without augmentation [17]. Out of that % how many labour without an epidural or other medication? Out of that % how many are birthing in the conditions described above? I pose the questions because these stats are not presented.

Most women have medical interventions during birth that interfere with their oxytocin release. In these cases, active management of the placenta will reduce their chance of having a PPH.

Summary

Active management of the placenta will reduce the chance of a PPH in a setting that does not support physiology and in which routine intervention is the norm. Further options within active management can be negotiated (see above). Physiological placental birth is an option, and possible if you manage to avoid induction, augmentation, an epidural or complications and have a care provider who is experienced in expectant management.

Further Resources

You can find more information on this topic in my Fluid Early Integration Phase Lesson Package or Reclaiming Childbirth Collective.

Related blog posts

- The Placenta: essential resuscitation equipment

- Cord Blood Collection: confessions of a vampire midwife

References

- WHO (2024) Maternal mortality

- Belghiti et al. (2011) Oxytocin during labour and risk of severe postpartum haemorrhage

- Phaneuf et al. (2000) Loss of myometrial oxytocin receptors during oxytocin-induced and oxytocin- augmented labour

- Kearney et al. (2019) Third stage of labour management practices

- Soltani et al. (2010) Administration of uterotonic drugs before and after placental delivery as part of the management of the third stage of labour following vaginal birth

- McDonald et al. (2013) Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes

- Rana et al. (2019) Delayed cord clamping was not associated with an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia on the day of birth or jaundice in the first 4 weeks

- Gülmezoglu et al. (2012) Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction

- Deneux-Tharaux et al. (2013) Effect of routine controlled cord traction as part of the active management of the third stage of labour on postpartum haemorrhage

- Begley et al. (2019) Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour

- Salati et al. (2019) Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage

- Reed et al. (2019) Birthing the placenta: women's decisions and experiences

- Fahy et al. (2010) Holistic physiological care compared with active management of the third stage of labour for women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage

- Davis et al. (2012) Risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage in low-risk childbearing women in New Zealand

- Saxton et al. (2015) Does skin-to-skin contact and breast feeding at birth affect the rate of primary postpartum haemorrhage

- Nove et al. (2012) Comparing the odds of postpartum haemorrhage in planned homebirth against planned hospital birth

- AIHW Australia's mothers and babies report

Join my mailing list to receive a monthly newsletter containing updates, evidence-based information, musings, rants and other goodies.

You will be sent a confirmation email. If you don't see an email from me in your inbox, check your junk folder and mark my email as 'not spam'.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.